Fat Souls

Note

In the early 1990s, I undertook an undergraduate degree by Independent Study at what was then Polytechnic of East London. Independent Study was an American concept, adopted at the time by a handful of British institutions. The individual student would put together their own curriculum, working with a supervisor. I initially chose to study ‘Theatre as Provocation, Ritual and Catharsis’. This morphed into ‘Theatre as Stage Poetry’. I wrote Fat Souls as part of the course, during the second year. I entered it into a competition at the Warehouse Theatre in Croydon in 1992 and it was that year’s winner.

My supervisor at East London was Malcolm Hay, co-author of an excellent book on Edward Bond and long-time comedy editor at Time Out. I showed him my most recent plays, the World trilogy, which he had positive things to say about as well as asking a provocative question, “is the world really this hopeless.” At the same time, I was assailed by powerful dreams asking me the same thing. The World trilogy was about the world, the flesh, and the devil. If I was to find hope, it couldn’t be in those things.

I was writing a play called Fat As You Like based on experiences working in an office in the 1980s. A lot of abuse was meted out to one of the women who worked there. So, my character Fat Mags. I wanted to move from the verbose and speech-driven World plays Steven Berkoff inspired me. I began to write Fat Souls in jagged, spikey, rhythmic verse. I envied composers and songwriters their license to versify. Wasn’t this also a privilege of dramatists?

Fat Mags’s story was as seemingly hopeless as those of the World plays. What could give it optimism? I conceived her gentle friend. I knew that the world would kill him. I grasped that her friend was Lamb. That hope could come from the shedding of his blood. That kindness lives on.

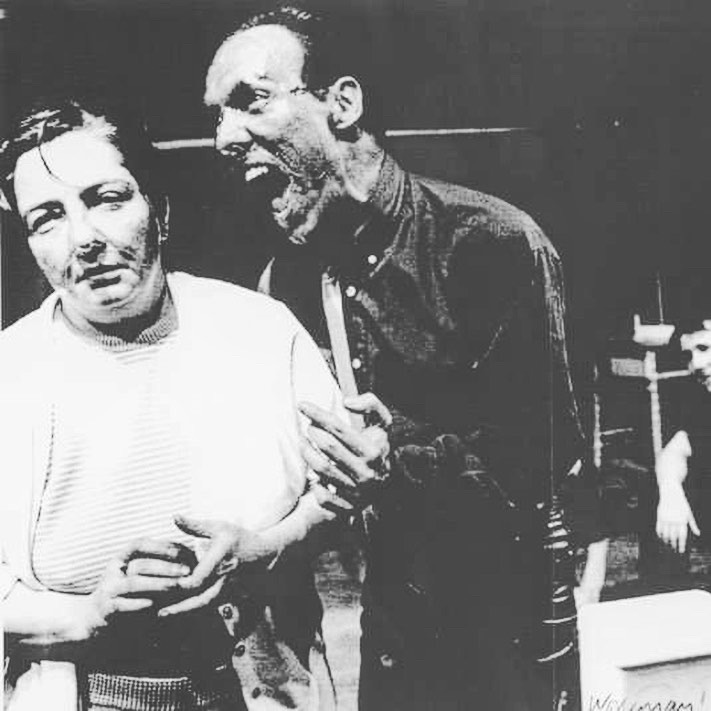

I put all the characters except Lamb and his Mother in masks. My study of the Greeks had given me an interest. In any case, who doesn’t wear one? ‘Person’ comes from the Greek for ‘actor's mask, character in a play.’ Some lines of Dylan about “an actor in a plot” and “take off your mask” tipped me over the edge. I committed myself to a crazy idea.

The other characters are a rough and ready lot of yobs, lackeys, climbers, lust pots, and keepers of secrets. They have a theatrical vitality and make Fat Souls into a kind of medieval canvas, swarming with hard and brutal life but with a calm centre within. I owe as much to Bosch and Breughel as any dramatist.

Fat Souls was a huge success. For once, the critics loved it. Audiences gushed. It was nominated for awards. It was published in Plays International (and later as a book). It got me a first agent. Enjoy your successes, fellow writers, for they are fleeting.

Story

Fat Souls is the story of a social misfit and long-time jobseeker, Fat Mags, who finds dead-end employment doing routine dogsbody work in an office. She meets Lamb, a youth with a whole other way of looking at things. His vision transforms her previously disconsolate outlook.

The office is peopled by a colourful array of characters. The office boss, Paterman, is a neurotic authoritarian whose mask conceals a closeted homosexuality lived vicariously through the promiscuous encounters of his more daring friend Froppage. Roar, the leonine cock-of-the-office whose sexual prowess and sports hero glory conceal a heart all too easily broken. Luce, the office secretary who hides a machinating ambition to succeed at any cost. Thumb, a nerd who hero worships Roar to the extent that his own self is scarcely existent. Barry BJ, the office bully whose intimidation of Fat Mags masks personal insecurity and a sad past.

In the midst of all of these masked figures crying "Me! Me! Me!" walks the gentle Lamb, quietly determined to get through his workdays doing no harm, bringing home the money needed to keep the garden he cultivates alive. To this garden, bequeathed by his late father, Lamb brings the long-suffering Mags. He takes off her masks and reveals his take on life.

But can such a fragile and idealistic vision of the world survive in a jungle where each man is hunting for himself. Especially when the lion roars in the rain in pain and rage?

Casting requirements: 5 m, 3 f (with doubling)

Production(s)

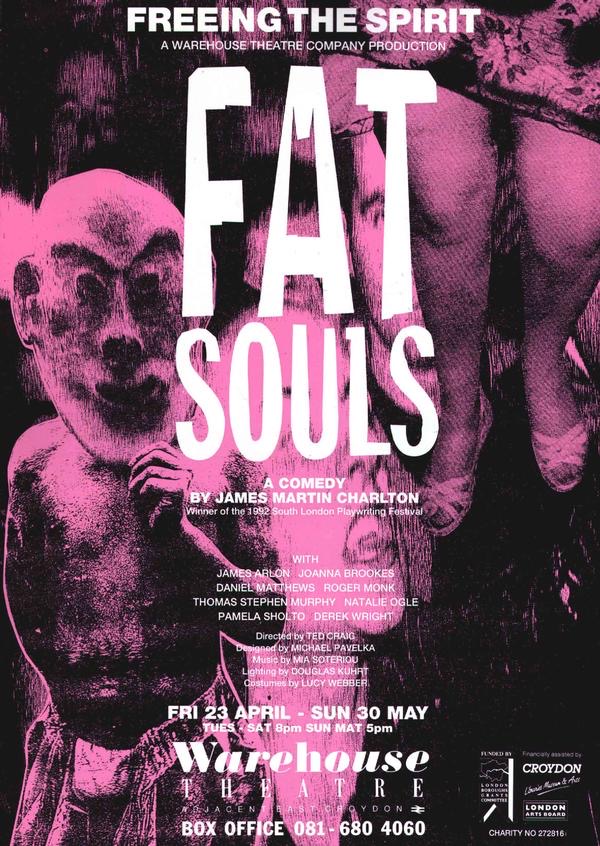

Reading: International Playwriting Festival at Warehouse Theatre, Croydon, 22 November, 1992

Cast: Joanna Brookes (Fat Mags), Raymond Coulthard (Lamb), Jason Isaacs (Roar), Rebecca Lacey (Luce), John Levitt (Paterman), Roger Monk (Barry BJ/Froppage), Thomas Stephen Murphy [Tom Hayes] (Thumb/Lenno), Pamela Sholto (Lamb’s Mum)

Directed by Richard Osborne

Produced by Warehouse Theatre Company

Premier: Warehouse Theatre Company at Warehouse Theatre, Croydon, 23 April-30 May, 1993

Cast: James Arlon (Roar), Joanna Brookes (Fat Mags), Daniel Matthews (Lamb), Roger Monk (Barry BJ/Froppage), Thomas Stephen Murphy [Tom Hayes] (Thumb/Lenno), Natalie Ogle (Luce), Pamela Sholto (Lamb’s Mother), Derek Wright (Paterman)

Directed by Ted Craig; designed by Michael Pavelka; lighting by Douglas Kuhrt; music by Mia Soteriou

Produced by Warehouse Theatre Company

Reading: North London Literary Festival at Middlesex University, 23 March, 2015

Cast: Andreas Angelis (Thumb/Lenno), Zoe Biles (Luce), Sam Caseley (Lamb), James Esler (Roar), Alyn Gwyndaf (Paterman), Kevin Kinson (Barry BJ/Froppage), Helen Minassian (Lamb’s Mother), Ells Smith-Fallon (Fat Mags)

Directed by Connor Abbott

Produced by North London Literary Festival

Press/Audience Reaction

“Fat Souls was one of the most innovative and original plays I can remember seeing in a long history of going to see new plays." - Michael Codron

"THERE is simply no mistaking a new voice in the theatre. The evidence is not restricted to what the characters say: in this case, a fancy use of street argot veering into rhymed couplets, no less; and veering that way, not to carry some elevated thought, but any old time, just whenever James Martin Charlton, the 26-year-old author, likes the idea. Nor is it necessarily what his characters do that announces a writer's arrival. Charlton's central character is a fat lump of a girl who learns to brave the sneers of fellow workers in her first office job; she encounters happiness, loses it, and maybe at the end finds relief tending her lover's garden. Well, this is original but not tremendously so. The use Charlton makes of masks is novel. Masks? Yes, the play is about hiding behind them and taking them off, which is certainly uncommon. But not unmistakable proof of quality. This proof comes from the charge that animates the cast. Whether playing bully, siren, nerd, saint, boss or fat lump (a captivating performance by Joanna Brookes), the actors know this is good meat to sink their creative teeth into. The director, Ted Craig, knows it, and everybody involved – audience too – shares that confidence. The play won the 1992 South London Playwriting Festival, an oddly named event, since one of the entries came from Africa, though this is undeniably south of London. The name refers to Craig's theatre, which judges the entries and stages the winner. He is doing his playwrights, and the theatre at large, a fine service. The adventures of Fat Mags are performed within and in front of a metal pyramid (de signer: Michael Pavelka), equipped with sliding panels and an upper level. Mags is first seen in a pose resembling a Rokeby Venus who has overdosed on doughnuts, morosely criticising her heavy thighs and bouncing breasts. However, cheerfulness keeps breaking through. "Positivity," she declares, snapping home the elastic of her tights and setting off for her job interview. Doubts unnerve her and she puts on her transparent half-mask, to hide her vulnerable self. All but one of the people she meets are masked, removing them when speaking from the heart, but sliding them into position when anxiety defends itself by posing. Charlton knows that many people in the world are nasty, brutish and short-tempered. He gives them ugly feelings to express, and their habit of speaking in short, rhythmic phrases, something like pentameters, unselfconsciously posturing, elevates them to super-realist status. Charlton's is a quirky, assured creative voice, edging at times towards sentimentality but consistently theatrical." - Jeremy Kingston, The Times

"In Fat Souls, James Martin Charlton tells the story of Fat Mags (the splendid Joanna Brookes), who takes a job as office dogsbody hoping to find life and' love, only to be spurned and humiliated by a pack of preening studs who are inwardly as wretched as she is (hence the title). Told through cartoon characters and telegraphic verse, this remarkable piece delivers a parable on the need to confront the world without a mask. The author certainly does so. He does nothing to defend himself against sneers for sentimentality and naive Christian uplift, and they do him no damage. He has created something funny, touching, and quite unlike anything else on the scene." - Irving Wardle, The Independent on Sunday

"…a new playwright of great promise… a confident new theatrical voice… energy, street language and dives into rhyming verse." - Ned Sherrin, Sunday Express

"It’s a simple story, but a remarkable one. Charlton writes with energy and jauntiness, strapping ancient dramatic traditions to his modern tale with great success - the play is written in verse and the characters wear masks, yet this never appears gauche… evocative of Jonson in its relish for stereotype… a play about the redemptive power of love with distinctly Christian undertones, yet it is never mawkish, rather it is funny, touching and enjoyably theatrical." - Sarah Hemming, The Independent

"…sparkles with originality and life… Fat Souls, with its masks and preoccupation with the truth behind the hidden, is written almost entirely in a form of rhyming prose poetry that explodes as if Caryl Churchill and Ben Jonson had suddenly rubbed shoulders… An exciting and thrilling debut indeed." - Carole Woddis, What’s On

"…visceral theatre in the Greek tradition… this is a play to be torn off and swallowed whole in bleeding chunks." - Time Out

"...compulsive... It is no accident that this saviour is called Lamb and biblical parallels are evident throughout the plot... This is a fascinating, stimulating play which grows in stature the more you think about it. It's very much more than a 'comedy'. It's a challenging piece of theatre with a lot to say." - Diana Eccleston, Croydon Advertiser

"Most people yearn to be popular and Fat Mags is no exception. Her overweight body has prevented her from achieving her aims in life job, friends, a lover. But when she is offered her first position in an office, she grabs at the chance to find happiness... Her attempts to make friends with her co-workers backfire, however, and so, rejected, she puts on a brave front and tries to pretend she doesn't mind. But a colleague who is also an outsider at work because he is thought to be "queer" invites Fat Mags into his secret world, where she begins to understand she doesn't need to be anyone other than who she is to be happy. Mags is not the only one with problems, however. Each character wears a' "mask" in the office to conceal their true feelings and problems from the others to the extent that practically no one has any idea about anyone else's real life. Playwright James Martin Charlton was a joint winner of this year's South London Playwriting Festival with this play. Fat Mags is primarily a drama, dealing as it does with human insecurities; fear, prejudice and loneliness. But these heavy themes are balanced by plenty laughs as the audience recognizes their own foibles or feelings expressed by the characters. Charlton displays an accurate ear for dialogue and manages to create characters whom we care about... a strong piece of drama." - Gillian Button, Croydon Advertiser (on the 1992 reading)